RETRO – Thirty-two years ago, in 1988, Neuromancer was published, based on William Gibson’s world-famous novel of the same name, which launched the entire cyberpunk genre.

“The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” With this sentence, William Gibson‘s terrifying science fiction vision was launched on its world tour. It was the beginning of the process that today culminates in the Matrix trilogy. It was with this sentence that cyberpunk was born in 1984. And it was the very same sentence that launched the world’s first cyberpunk adventure game, the adaptation of the same name, Neuromancer, published four years later.

A small personal confession: the novels of the Neuromancer trilogy (especially the very first part) are still to this day among my greatest science fiction novel experiences, and Neuromancer itself is also my favourite novel. I read the first book back in ’88, almost in one sitting, after playing through the Commodore 64 game.

William Gibson: father of the cyberpunk genre

Published in 1984 and translated into Hungarian as NeuroMachine (translated into English by Ajkay Örkény), William Gibson was the first pioneer of the cyberpunk genre. William Gibson never actually thought he would found a specific genre with his work, he himself (by his own admission) was not a computer and internet genius at all – so much so that he didn’t even own a computer, he wrote the novel on a traditional typewriter. However, the novel was a huge success, winning both the Nebula Award, the Hugo Award and the Philip K. Dick Memorial Award, and Gibson himself wrote sequels to it, entitled Counting to Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive.

Gibson was later a little irritated by the huge cyberpunk fad and craze that started in the late eighties and early nineties in the wake of his novel – in particular Billy Idol’s 1993 album ‘Cyberpunk‘ and the music video for its most famous track, Shock to the System (see below), which he called downright ‘silly’.

William Gibson himself later wrote other cyberpunk novels, and in some of his novels he also tried his hand at steampunk, but his most famous novel to date is 1984’s Neuromacrochet. The now 72-year-old author has published another novel this year, Agency, which takes us to an alternative 2017 in which Hillary Clinton won the election (a sequel to The Peripheral).

Timothy Leary, the LSD Pope, “gets in on the action”

The rights to Neuromancer were acquired by the famous psychologist gentleman above, who was a famous promoter of the LSD drug. He wanted to make both a movie from the novel (the former was never made, you can see the promo for the movie below, featuring a young William Gibson) and a video game.

The psychologist, an LSD enthusiast, imagined the video game as a companion to the NeuroMovie, and initially thought of it as a kind of interactive novel. The script for the film would be written by none other than the legendary William S. Burroughs (Naked Lunch), known for his drug novels, and the music for the film (which was eventually completed and two different versions of the incredibly catchy digital version were included in the game) would be composed by the progressive band Devo. You can listen to the original version of Devo: Some Things Never Change here:

It’s not clear why the film didn’t work out, unfortunately information about it has since been lost, partly because Timothy Leary died in 1996.

Creator: the Interplay

Whatever happened, Timothy Leary eventually sold the rights to Activision, which was then called “Mediagenic”, and instead of the original “interactive novel” concept, the development of a very different kind of game began, thankfully. The game was developed by Interplay, then in its heyday, and produced by the now legendary Brian Fargo. The team had previously developed Wasteland, so they didn’t hire a bunch of rookie developers. The game’s lead programmer and lead developer was Troy A. Miles (his name is on the title screen), and the others were: Developers Michael A. Stackpole and Bruce Balfour, and graphic designer Charles H. Weidman III (Stackpole’s name is also known from the Battletech novels). For the game’s theme music, a very unique digitalisation solution somehow squeezed in Devo’s Some Things Never Change, linked above, and the result was strangely eerie on Commodore 64 (though you couldn’t listen to it for long):

The game’s only musical insert explored the same theme, but in a much more atmospheric, catchy way, making the most of the Commodore 64’s music chip.

There was a PC version and a Commodore Amiga version – the latter with much better graphics, but the music part was not really well done, it was much weaker there (and on PC only the whistling was left, since we were still in the era before sound cards were available).

The game received very good reviews, and was one of the best of the year in several gamer magazines.

So how was Neuromancer?

The genre was a traditional adventure game, which at first was very reminiscent of LucasArts’ then hugely popular Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken’s point’n’click adventure games. I remember a C64 friend of mine in ’88 introducing it as “it’s like Zak McKracken, but a bit more unique and interesting.” The game starts with the now-iconic “television screen heaven”, although our freely-named hero wakes up in a much less serious mood: specifically, lying in a bowl of spaghetti. Part crawling, talking, information-gathering and acquiring various skill chips and software (these will become significant later), the half-adventure, half-simplified RPG took Gibson’s work part seriously, part parody (of course, the enormous respect and adoration for the novel came through), taking on typical cyberpunk themes that will recur not only in the original book but also in Cyberpunk 2077, which will be released this November: huge corporations trying to dominate the whole world – fighting each other – organ harvesting and the use of special prostheses, and of course the “Matrix” itself, a kind of imagined “precursor” to today’s internet, which we could only imagine in 1988.

In addition, the humour of the game was incredibly stylish and well-timed, with plenty of pop culture references, such as Pong being the “one true video game” and religiously revered, but we also got nods to classic sci-fi like 2001: A Space Odyssey.

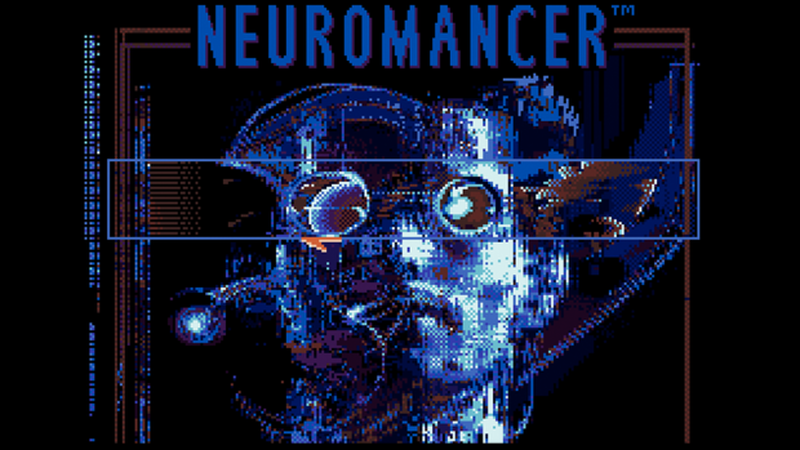

What is the Matrix?

No, the Wachoski brothers’ (later: sisters’) films didn’t even exist at the level of the imagination, the Matrix was a one-to-one representation of the cyberspace that existed in the virtual reality invented by William Gibson, using the video game tools of the time. A kind of ‘action-RPG’ part of the game actually prevailed here: we could fight the defensive programs called the AI, or the artificial intelligences personified by faces (the AI itself was the main enemy in the end), according to whether we could get the various versions of the attacking, hacking programs beforehand. It was this cyberspace combat – somewhat reminiscent of the magic system in role-playing games – that made Neuromancer a very special game, really surpassing the Lucasfilm and Sierra On Line point’n’click adventure games of the time.

Video game classic

Although Neuromancer is not as well known as the adventure games of the other two companies, it is now considered a classic for its unique gameplay, atmosphere and, in particular, as the only adaptation of the William Gibson novel. It was also the very first cyberpunk-themed game – a kind of precursor to the great cyberpunk craze of the 1990s and, of course, to Cyberpunk 2077, which will be released this November.

-BadSector-

Publisher: Electronic Arts, Activision, Interplay Entertainment, Electronic Arts Ltd

Developer: Interplay Entertainment

Style: Adventure game

Release date: 1988

Leave a Reply