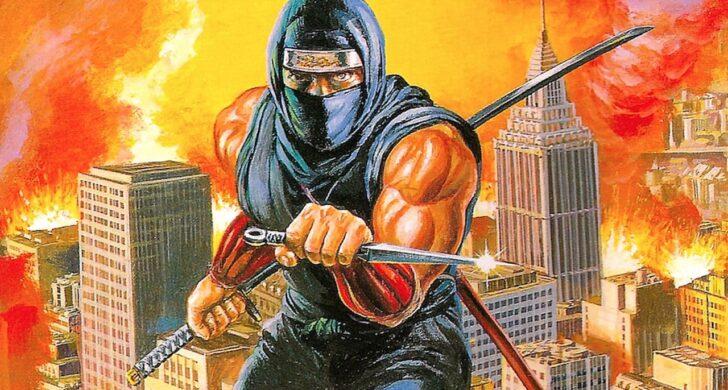

RETRO — Ryu Hayabusa heads to America to uncover the truth behind his father’s mysterious death; a personal vendetta turns, in a heartbeat, into a globe-spanning occult fiasco: two demonic statues, a lunar eclipse, and a zealot named Jaquio pulling the strings — all in an NES classic that launched in 1988, made history with long, anime-style cutscenes, and earned a reputation for its punishing difficulty.

Ninja Gaiden (in Japan: Ninja Ryūkenden) debuted on the Famicom/NES in late 1988; it reached North America the following spring, and — thanks to squeamishness over the word “ninja” — landed in Europe in August 1991 under the title Shadow Warriors. Tecmo didn’t simply ship an arcade port: under the same name, two separate projects ran in parallel — an arcade beat ’em up and this console platformer — handled by different teams. The result was an 8-bit “cartridge movie” that paired gameplay with cinematic storytelling while cranking the challenge up to legendary.

Design Ethos and the Tecmo Theater (Origins, Renaming, Presentation)

The NES version was directed by Hideo Yoshizawa, with Masato Katō as the key visual lead; the music was composed by Keiji Yamagishi and Ryuichi Nitta. The team’s philosophy was straightforward: if a game wasn’t tough enough, it would gather dust on the shelf. Level design behaves like sheet music — platforms, lamps, and walls are beats you must hit on time. The setups didn’t shy away from difficulty yet stayed consistent: when you make a mistake, you learn something for the next run. The Tecmo Theater delivered the breakthrough in storytelling: over twenty minutes of anime-flavored cutscenes — close-ups, hard cuts, distinct musical cues — that turned transitions between Acts into full-blown scenes. Large, manga-style panels filled the top of the frame with dialogue below — just enough “film” to give pre- and post-boss moments real weight.

The name change tells a story, too: the Japanese Ryūkenden — roughly “Legend of the Dragon Sword” — became Ninja Gaiden in the West because it simply sounded right; in Europe it was Shadow Warriors, where the mood of the era avoided the “ninja” label. The game appeared with a flashy booth at Winter CES ’89, and Nintendo Power pulled players in with covers and multi-page guides. Localization was its own stunt: text burned into image files, strict character limits, and do-not-use lists — yet the English still had to snap and pop. One later-infamous “bug turned design choice” remained as well: fail during the closing boss trio and you’re kicked back to the beginning of Act 6.

Rhythmic Cruelty: Mechanics, Bosses, and the Lessons of “Nintendo Hard”

This is a side-scrolling action-platformer built around six Acts and twenty stages. Ryu’s primary weapon is the Dragon Sword; the secondary arsenal includes the Shuriken, the returning-boomerang Windmill Shuriken, the iconic Art of the Fire Wheel, and the aerial-carving Jump & Slash. All of it runs on “Spirit” (Ninpo), replenished via red/blue orbs. Lamps can drop an hourglass (a global freeze for a few seconds), healing items, a temporary “Invincible Fire Wheel,” and even 1-UPs. The wall-kick “bounce” is the heartbeat of the game: it’s not simple climbing but rhythm-keeping. Spawn points and enemies parked on screen edges deliberately test your timing; slip off the beat and the infamous hawk or a bat-wielding goon will tag you — and you’re already falling.

Every Act ends with a boss. From Jaquio’s court, the “Malice Four” (Barbarian, Bomberhead, Basaquer, Bloody Malth) function as mechanical exams: one demands wall rhythm, another disciplined weapon switching, a third precise positioning, and the fourth patience under pressure. The grand finale — lunar eclipse, paternal melodrama, demon awakening — is pulp and operatic at once, and this is where the notorious “send-back” kicks in: fail at the finish and you’re marched down the penalty staircase. Infuriating? Absolutely. But it forges the finger memory and timing that the game has been drilling since the very first screen. That’s why the “Nintendo Hard” label stuck: the difficulty isn’t there to grief you — it’s there to teach you.

Meanwhile, the plot is surprisingly personal. Jaquio turns Ryu’s father, Ken Hayabusa, into a puppet (the Masked Devil); smashing the crystal orb breaks the control, while the eclipse summons the demon (Jashin). In the closing scene, Irene Lew’s name “enters the frame,” and sunrise puts a clean period on the tale — all wrapped in cutscenes that defined how to tell a “film-like” story in the 8-bit era.

Hype, Honors, and Afterlife (Reception, Ports, Music)

In the summer and fall of 1989, the game settled at #3 on Nintendo Power’s Top 30, while Electronic Gaming Monthly kept it in the top ranks for months — and by year’s end it took home the NES category’s grand prize and “Best Ending.” Later it became a regular on “hardest games” lists, thanks in no small part to that infamous Act 6 and the enemy placements wired to the screen’s edges. In the Virtual Console era, critics consistently highlighted its pioneering storytelling and driving score (IGN, Nintendo World Report, and others called it out).

The ports arrived in waves over time: the PC Engine release in the early ’90s brought a richer palette and a different timbre; the Ninja Gaiden Trilogy on SNES repackaged the trilogy midway through the decade; from the mid-2000s, the Virtual Console and later the mini-consoles (NES Classic) carried the torch, followed by convenient access via Nintendo Switch Online. A mobile, episodic experiment kicked off with the first game, though the sequels never materialized. Among tie-ins, Scholastic’s Worlds of Power paperback wrote a “kid-friendly” ending, while Dark Horse’s comic echoed the classic five-part arc. On the music front, after the original CD release, Yamagishi’s melodies eventually returned on vinyl — no surprise: these themes set a BPM that’s still easy to lock into today.

Big picture, Ninja Gaiden stayed a gold standard because it never leaned on a single trick. Wall-jumps shine where level rhythm gives them purpose; cutscenes hit hardest when the gameplay’s pulse is peaking; and the difficulty isn’t a joyless whip but a coherent training ground. Pop it in today and the first things you’ll notice are the visual clarity and the taut input — and when the final boss finally collapses, “CLEAR” clings to the screen the same way endorphins cling to your grin. From that angle, the “cartridge movie” isn’t a museum piece; it’s a living rhythm — fall into step and it carries you along.

— Gergely Herpai “BadSector” —

![Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines – Prepare for Your Final Sunset! [RETRO-2004]](https://thegeek.games/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/theGeek-Vampire-the-Masquerade-Bloodlines-302x180.jpg)

Leave a Reply