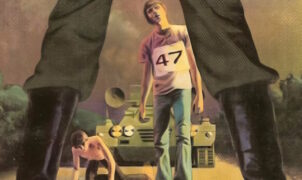

RETRO FILM – With Tyrone Power in the lead role, the first adaptation had to find a way to tell the dark story of a con man’s career without offending the censors. Yet the 1947 film is darker and more brutal than the newer version in some ways.

At this month’s premiere of his new drama Nightmare Alley, director Guillermo del Toro said he read William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel – the official source material for the film – before watching the classic 1947 adaptation with Tyrone Power. But there’s no question that the first film significantly influenced del Toro and Kim Morgan, who co-wrote the script. The last sentence is taken directly from the original script, penned by Jules Furthman.

As in the new version, the 1947 version follows the life of Stan, an ambitious carnival worker who wants to break out of his social class. Stan (played by Tyrone Power, now played by Bradley Cooper) learns (or rather steals) a few tricks from a down-and-out carnival couple, Zeena and Pete, whose former greater ambitions have been reduced to a bit of fairground routine. Eventually, Stan elopes with a co-worker, Molly, and they embark on a mentalist show aimed at Chicago’s upper class.

A great classic by a not very talented director

The film has long been a favourite of retro film fans and noir festivals. But its lasting appeal is not easy to define.

Certainly not because of the director: the British-born Edmund Goulding (“Grand Hotel”), whom Andrew Sarris, in his groundbreaking survey of Hollywood filmmakers, American Cinema, categorised as “unsympathetic”: “directors of fluctuating talent, strangely saved by their lack of pretension”. Sarris noted that even Goulding’s best films, including Nightmare Alley, were rarely considered his own and pointed out that Grand Hotel won the Best Picture award without a director’s nomination.

Sarris has also called Goulding’s career “discreet and tasteful”, but the Nightmare Alley is hardly that. In an extra for the Criterion Channel, Imogen Sara Smith, author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City, notes that Goulding may have had an unexpected affinity for the material. She says she had “quite a scandalous reputation” in her private life, adding that she “struggled with alcoholism and drugs, and was rumoured to have hosted wild bisexual orgies”.

The fateful, “predestined” social class

“Nightmare Alley”, made under the restrictions of the Production Code, could never have featured anything so filthy. But it’s a dark and cynical film and an excellent stylistic exercise for film noir; a category that somehow defies a clear definition of the genre. As written many times, noir is not quite a genre, mood or style. “Nightmare Alley” is not a mystery, nor even really a thriller. But it does evoke a soul-crushing sensation that runs through your system like methanol poisoning one of its characters. The sense of fatalism, a fundamental element of noir, is omnipresent. ”

The original film is not subtle in its depiction of social class as an inevitable, fateful existence. It becomes clear from the beginning of the movie that Zeena and Pete (Joan Blondell and Ian Keith) have ‘been in a big-time but have returned to their ‘natural place’: an unsatisfying life of wandering carnival work, where Zeena performs a mind-reading act while the ever-drunk Pete provides clandestine assistance. One of the main attractions of the carnival – and a stunt that impresses Stan – is the “geek” who bites the heads off live chickens. “I don’t understand how someone can sink so low,” Stan reacts at the beginning of the film, a reaction that simultaneously indicates his self-confidence and his poor situational awareness.

This femme fatale doesn’t flinch

When Stan finally meets the femme fatale, Dr Lilith Ritter (Helen Walker, played by Cate Blanchett in the 2021 film), it is significant that she is a psychologist – not only someone who understands what Stan is thirsting for, but also someone with money and status, which gives her an essential advantage over Stan as a con man. (Blanchett’s introduction is just another element that del Toro borrows from Goulding’s film rather than the novel.)

While in the new film, Zeena approaches Stan, the 1947 adaptation had to be more purposeful. There is real sexual tension in the simple moment when Power kisses Blondell’s arm, and he returns the kiss with a caress. But for Stan, in the 1947 version, even more than in the book or the new film, sex seems to be a little interest. “I don’t even look at another guy. Never,” Molly (Coleen Gray) promises him after their wedding. But the moment she makes that promise, it’s actually Stan who isn’t even looking at her. He stares off into the distance with his eyes twinkling and, like Donald Duck, with dollar bills in his eyes, thinks only of the money they will make together.

Threatening shadows, Chicago just a set

Lee Garmes’s cinematography isn’t full of the smoky, disingenuous shots Garmes did for Josef von Sternberg in Dishonored or The Shanghai Express, but the crowded, tarpaulin-filled carnival set gave him ample opportunity to envelop the actors in menacing shadows. (On the rarely screened, incendiary nitrate films, Garmes’s images exude a particularly silvery chill.) Apart from two street shots of a taxi scene, Chicago is evoked almost entirely through set design, dialogue and rear projection. The placement of the actors – Power grinning slyly and unconcerned with the prospect of happy family life – is a move that suggests Goulding knew what she was doing.

Misconceptions and self-deception

What makes Nightmare Alley ultimately enduring is perhaps its suggestion that we are all prone to fall for delusion and self-delusion – and maybe even want to. In both films, the story’s climax is when Stan, nearing the bottom of the downward spiral, suddenly realises he has become a sucker.

Although del Toro’s updated version adds details from the novel that would not have passed censorship in 1947 and closes the film in a more emphatic, more concise way (while leaving much else out – such as the first section of the film, or exaggerating it), the 1947 version is the genuinely definitive and also the more cruel, more vicious adaptation of the classic novel.

-BadSector-

Nightmare Alley (1947)

Direction - 8.2

Actors - 8.4

Story - 8.2

Visuals (1947) - 7.8

Ambience - 8.2

8.2

EXCELLENT

What makes Nightmare Alley ultimately enduring is perhaps its suggestion that we are all prone to fall for delusion and self-delusion - and maybe even want to. In both films, the story's climax is when Stan, nearing the bottom of the downward spiral, suddenly realises he has become a sucker. Although del Toro's updated version adds details from the novel that would not have passed censorship in 1947 and closes the film in a more emphatic, more concise way (while leaving much else out - such as the first section of the film, or exaggerating it), the 1947 version is the genuinely definitive and also the more cruel, more vicious adaptation of the classic novel.

Leave a Reply