RETRO – Online role-playing games are more than just a form of entertainment. They have transformed how we communicate, love, grieve, spend money, and relax. World of Warcraft has not only had a massive impact on the gaming community but also on pop culture. Today marks the 20th anniversary of World of Warcraft, which was first released on November 23, 2004, in the United States and Australia.

Even if you’ve never immersed yourself in the battle for Azeroth between the Alliance and the Horde, chances are you’ve heard of World of Warcraft. This colorful online role-playing game, where orcs, blood elves, night elves, and dwarves band together to complete quests and defeat villains, has far exceeded the boundaries of gaming, becoming an integral part of pop culture.

World of Warcraft, published by Blizzard Entertainment in November 2004, quickly drew millions of subscribers paying monthly fees to join guilds, either with real-life friends or in hopes of meeting new ones. The game soon appeared in South Park and political campaigns, followed by the obligatory Hollywood adaptation. However, its influence extended into unexpected realms, such as cryptocurrency and epidemiology.

Although it is no longer at the peak of its popularity, World of Warcraft—commonly referred to by fans as WoW—remains strong. Its latest expansion, The War Within, was released this August. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, here are 20 examples of how it has shaped the world.

WoW Was a Social Network Before Social Media

World of Warcraft’s popularity eclipsed earlier giants of the genre, giving many their first taste of the future of online social networking. In its first year, Facebook was still limited to universities, and broadband internet was only beginning to become widespread in homes.

Gamers were accustomed to connecting with a few friends over online servers or local area networks (LAN) for first-person shooters or real-time strategy games. But stepping into WoW’s bustling capitals, where hundreds of players gathered, offered a wholly different experience.

“We’d often just log in and use it as the coolest chat room in the world,” said Ion Hazzikostas, who joined Blizzard in 2008 after spending long nights as a guild leader. “It was literally about seeing who was online and deciding what to do together.”

He added, “The guild I played with 20 years ago is still active.”

Politics Discovered WoW

This year, the Democratic Party used Vice President Kamala Harris’s Twitch account to host a World of Warcraft stream, paired with a Tim Walz rally, to engage young online voters.

Although the event attracted only around 5,000 viewers, it offered a more positive portrayal of the game than the Maine Republican Party did in 2012. Back then, a state senate candidate was criticized for writing online that her orc character, who operated as a rogue, enjoyed “stabbing things.” (The candidate ultimately won with 53% of the vote and served one term in office.)

South Park Won an Emmy for Its WoW Episode

The irreverent animated series created the “Make Love, Not Warcraft” episode in 2006, in which Cartman and his friends attempt to take down a vengeful high-level player. The Emmy-winning episode explored the game’s addictive nature and served as a meditation on media obsession in the pre-social media era.

In South Park, the obsession that glued players to their computers portrayed them as pimply, overweight addicts.

WoW Inspired Academic Studies

The game provided a unique setting for academic research, from analyzing war crimes and folklore theories to group behavior and religious conflicts within Azeroth.

WoW Proved Subscription Models Could Work

In the early 2000s, the gold standard for MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online role-playing games) was EverQuest, which peaked at nearly 550,000 players. Within a year of its 2004 launch, World of Warcraft had reached 5 million subscribers.

By 2010, the game hit its peak with 12 million subscribers, generating billions in revenue for Blizzard through monthly fees and in-game purchases.

“This made up a huge part of Blizzard’s revenue, and it still does,” said Jason Schreier, journalist and author of Press Reset. Schreier also cautioned about the downsides of focusing on a single game: “A stable source of income like this allows for innovation, but in practice, it often consumes all resources.”

WoW Made Orcs Heroes

When orcs appeared in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, they were brutal demons serving as cannon fodder in Sauron’s armies. Peter Jackson’s films reinforced this fearsome image in the 2000s.

World of Warcraft, however, rehabilitated the perception of orcs. Suddenly, these creatures could display heroism. Orcs, along with other “terrible” races, fought to survive in a world that feared them.

The Birth of a Meme: LEEEEROY JENKINS!

In 2005, during a dungeon strategy meeting, a player suddenly charged into a dragon-filled room yelling his name, “Leeroy Jenkins!” The reckless action proved disastrous—and, as it later turned out, staged—but its impact was real.

This was one of the first player-generated memes to break into mainstream culture. Leeroy Jenkins became a symbol of bold but ill-considered decisions, referenced in TV shows and even the U.S. Congress.

WoW Became a Tool for Epidemiology

In 2005, the uncontrollable spread of the Corrupted Blood debuff frustrated players but fascinated epidemiologists, who studied it as a case study.

The debuff, which damaged players for several seconds before spreading to others, escaped its intended jungle zone due to a programming glitch. Players were expected to die before spreading it too far, but portals, pets, and NPCs exacerbated the situation.

WoW’s community attempted voluntary quarantines and isolation measures, reminiscent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, but these efforts were insufficient. Ultimately, Blizzard had to reset the servers.

Celebrities Fell Under WoW’s Spell

When actor and comedian Robin Williams passed away in 2014, Blizzard honored him with an NPC: a genie referencing his role in Aladdin. This permanent tribute also highlighted how many celebrities were fans of the game.

Several stars openly discussed their WoW fandom on talk shows. Mila Kunis revealed she played a pink-haired frost mage, while Ronda Rousey and Vin Diesel played together nightly after filming Furious 7. Jamie Lee Curtis shared plans to officiate her daughter’s wedding dressed as a WoW character.

Henry Cavill even missed the call announcing his role as Superman because he was playing World of Warcraft. “I knew my priorities,” he told Conan O’Brien, adding, “I was in the middle of a very important dungeon.”

Steve Bannon and WoW’s Peripheral Economy

Impatient players unwilling to grind for hours could spend real money on virtual gold sold by specialized companies.

In 2007, Steve Bannon—later a political adviser to Donald J. Trump—joined a company that employed underpaid Chinese workers to farm gold. The company, Internet Gaming Entertainment, received $60 million in investments, including from Goldman Sachs.

Blizzard worked to ban the real-money sale of virtual gold. Bannon’s company faced lawsuits, restructured, and was eventually sold. Journalist Joshua Green wrote in Devil’s Bargain that this experience profoundly shaped Bannon’s strategies: “It provided a conceptual framework that he later used to build Breitbart News’s audience and mobilize online trolls and activists who flooded the national political stage.”

Players Opened Their Wallets for WoW Favorites

What fantasy adventure is complete without a loyal animal companion? WoW players could purchase pets and mounts for real money or earn them through in-game gold and quests.

Pets, such as the one-eyed Parrlok, were mostly cosmetic and served as adorable travel companions. Mounts, however, offered faster travel across the vast world. Newer mounts, like the $90 Trader’s Gilded Brutosaur, became widespread.

Despite already paying monthly subscription fees, the pet and mount market was unstoppable. “If we saw no one was interested in buying them, we probably wouldn’t have offered them,” said Holly Longdale, WoW’s executive producer. “But the demand was clearly massive.”

One rumor Longdale firmly denied was that sales of the shiny Celestial Steed mount ever surpassed the revenue of StarCraft II.

Great Games, Terrible Movies

The 2016 Warcraft film, directed by Duncan Jones (son of David Bowie), was a critical failure in the U.S., though it was saved financially by the Chinese market. The movie joined the canon of bad video game adaptations, beginning with Super Mario Bros. in 1993 and continuing with films like the 2024 Borderlands movie.

WoW Slang Infiltrated Far-Right Culture

Kek, a fictional frog-like deity satirically revered in certain online far-right circles, traces its origins to WoW. When players from opposing factions communicated in public chat, their messages were distorted. Horde players typing “lol” appeared as “kek” to Alliance players.

“The term spread from in-game chat rooms to forums like 4chan and Reddit, known hubs of far-right culture,” wrote the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups.

“I’m a Night Elf Mohican!”

Aubrey Plaza was one of several celebrities featured in World of Warcraft TV commercials, a rare instance of video games being advertised on television at the time.

“Some people think it’s cool to be in a Revlon hair product commercial,” Plaza told Vulture in 2012. “I think that’s embarrassing, but a World of Warcraft ad? That’s not embarrassing. That’s super cool.”

Cryptocurrencies Were Inspired by WoW

Critics often accuse cryptocurrency developers of gamifying finance, but the reverse is also true. Ethereum, one of the most well-known blockchains, has roots in WoW.

Ethereum creator Vitalik Buterin quit the game in 2010 after a patch weakened his warlock’s Siphon Life spell, an event he said brought him to tears. “That night, I realized how horrible centralized systems can be,” he later wrote in a blog post.

Three years after quitting WoW, Buterin delved into the world of cryptocurrencies.

In 2022, Buterin and two collaborators proposed a blockchain concept called soulbound tokens, an online verification system where issuers could “burn” tokens if recipients violated their trust. The idea was inspired by WoW’s soulbound items—non-transferable objects earned through challenging quests or defeating powerful enemies.

WoW Was a Welcoming Space for Many Women

Women have been an integral part of the WoW community since its inception. A 2009 Nielsen report found that WoW was the most popular game among female players aged 25–54.

Many PvP games (player versus player) tend to provoke negative emotions, like trash talk. While WoW isn’t immune to such behavior, it generally fosters a cooperative, environment-based experience where players work toward shared goals. Like-minded players could form guilds to collaborate in dungeons or role-play, shielding themselves from more aggressive playstyles.

“People choose this,” said Holly Longdale. “It’s not mandatory. This creates opportunities for safety and comfort.”

WoW Bridged Physical and Virtual Worlds

Long before QR codes appeared on restaurant menus, Blizzard connected tangible and virtual worlds through the World of Warcraft Trading Card Game, which ran from 2006 to 2013. Scratch-off codes on collectible cards could be redeemed for in-game rewards.

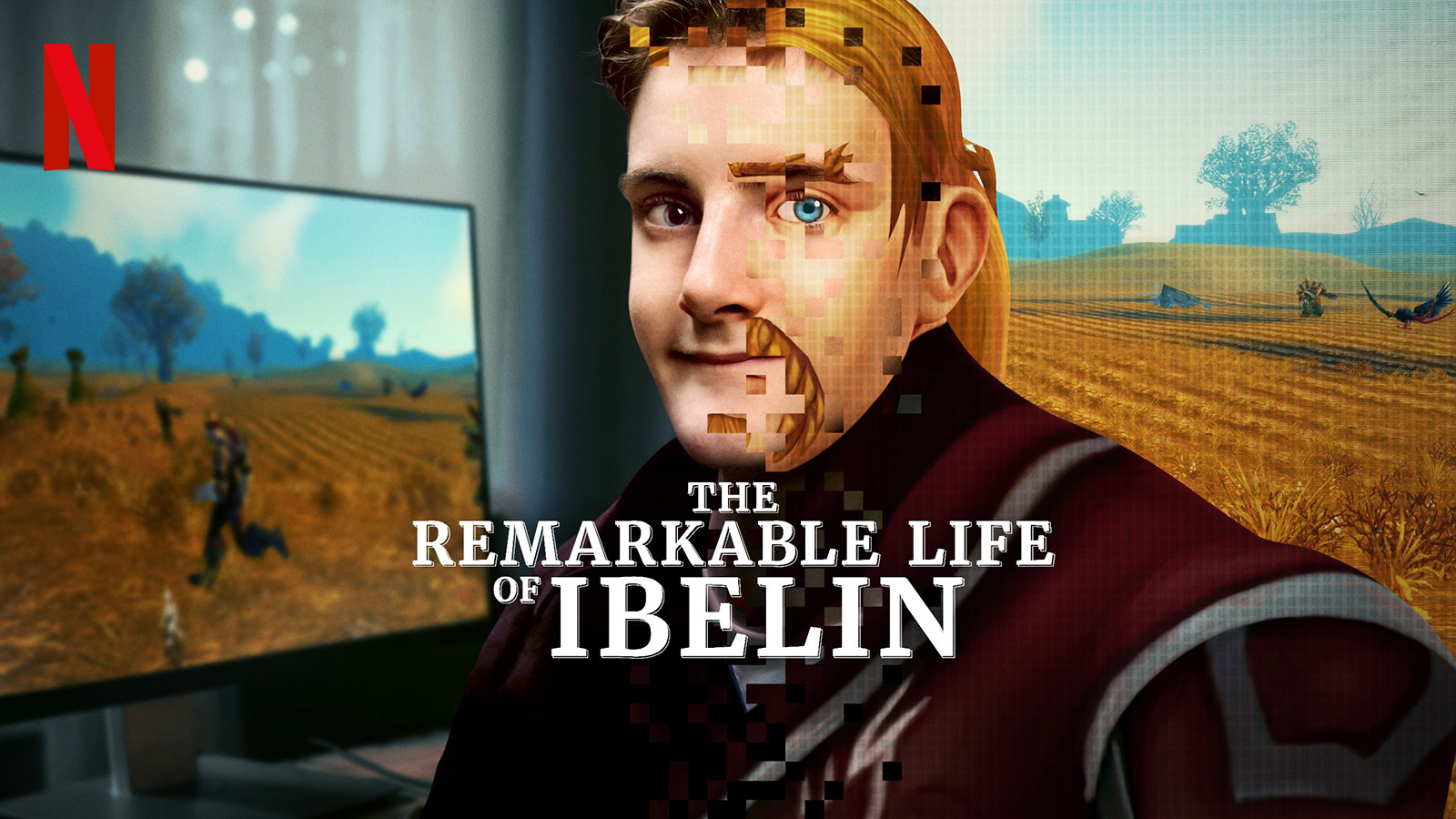

WoW Was a Place for Love and Mourning

WoW’s guild system allowed players to unite forces against bosses that dropped valuable loot upon defeat. Regular gaming sessions after school or work often forged relationships that extended beyond Azeroth, with many finding real-life romantic partners.

One particularly moving example is featured in the Netflix documentary The Remarkable Life of Ibelin, released in October. Mats Steen’s parents thought their son, who had a degenerative muscular disease, had few friends because he spent most of his time gaming at home. When they announced on his blog that Mats had passed away at 25, they were overwhelmed by the outpouring of condolences and support from his guildmates. Many of Mats’s online friends traveled to Norway to attend his funeral.

WoW Gave Artists a Virtual Stage

Angela Washko, an artist interested in social practices, discovered WoW around 2005 and was captivated by the virtual world’s ability to foster deep player connections.

But in the game’s darker corners, strangers hurled sexist insults at her during voice chats. “They immediately started spamming things like, ‘Go back to the kitchen and make me a sandwich,’” Washko said.

In 2012, she launched a four-year project titled The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft. This virtual performance art involved initiating political and social debates in the game’s capital cities. Washko said her work was ahead of its time, before society widely acknowledged the intertwining of virtual and real-life politics.

“The council provided an opportunity,” she said, “to discuss why the politics of daily life offscreen became even more pronounced and extreme in the relatively unregulated space of the game.”

WoW Tapped Into the Power of Nostalgia

Missing the good old days? Many WoW fans did—so Blizzard brought them back.

In 2019, after years of fan demand, the company released World of Warcraft Classic, stripping away expansions, gameplay updates, and modern graphics accumulated over the years.

“When we look at other forms of media, we usually remaster or create HD versions, like colorized adaptations,” said Nick Bowman, a communication professor at Syracuse University who studies gaming nostalgia. “It’s rare to say, ‘Here’s the original Metropolis from the 1920s, untouched.’”

Nostalgia plays an increasing role as the average gamer ages. Immersive games like WoW create deep connections and memories. WoW, Bowman said, “is probably the closest thing we’ve had to a metaverse.”

“Twenty years means some people have two hometowns—the one they physically live in and Orgrimmar,” he added, referencing the Horde’s in-game capital.

-Gergely Herpai, “BadSector”-

![Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines – Prepare for Your Final Sunset! [RETRO-2004]](https://thegeek.games/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/theGeek-Vampire-the-Masquerade-Bloodlines-302x180.jpg)

Leave a Reply