RETRO MOVIE REVIEW – An art history professor once told me that a worn-out sneaker is always a more interesting subject to draw than a brand-new pair. That thought came to mind as I rewatched The French Connection just before the Oscars.

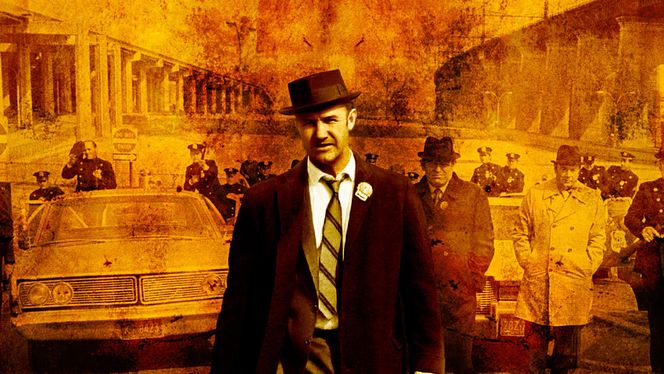

The film became legendary for its raw, unfiltered adaptation of Robin Moore’s novel. It follows two New York detectives on a relentless pursuit of a French drug syndicate, determined to stop a massive heroin shipment from flooding the United States. The film didn’t just turn Gene Hackman into an international star—it also delivered one of the most iconic car chases in cinema history. But looking back 45 years later, what’s equally remarkable is how director William Friedkin and cinematographer Owen Roizman captured the grime and decay of 1970s New York. The city’s cracked streets serve as a brutal portrait of the social and public health crisis that fueled drug addiction.

The French Connection is a testament to the allure of ugliness: a world revealed through Friedkin’s deliberate location choices and the unforgiving perspective of its main character.

A Relentless Antihero

Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle is based on a real-life detective—Eddie Egan, who, along with his partner Sonny Grosso, was the central figure in Robin Moore’s book. In the film, Doyle and his partner, Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (played by Roy Scheider), rely on a mix of instinct and relentless police work as they try to take down French crime lord Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey) before his heroin floods American streets.

Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle is an abrasive, deeply flawed character. He’s racist, drinks excessively, and treats women like disposable trophies. But his obsession with catching Charnier is both admirable and terrifying—he’s so hell-bent on the chase that he has no problem endangering his fellow officers or innocent bystanders. To him, the law is secondary. His only goal is to catch his target, no matter the cost.

Doyle is the polar opposite of Richard Roundtree’s Shaft, released just months earlier. While John Shaft exudes effortless cool, Popeye Doyle is a volatile wrecking ball, charging through anyone and anything in his way. He’s incapable of empathy, and the destruction he leaves in his wake is what makes him so compelling. He’s the kind of antihero you can’t look away from—much like Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry, which hit theaters only two months later.

One of the film’s most iconic sequences follows Doyle as he hunts down a hitman, Pierre Nicoli, sent by Charnier to eliminate him. Even if you’ve never seen the movie, chances are you’ve heard of the legendary car chase that ends with a deadly showdown on a subway station staircase.

But just as unforgettable is the way Doyle kills Nicoli—shooting him in the back. In the film’s Blu-ray commentary, William Friedkin explains why this moment was crucial: the execution-style shot perfectly encapsulates Doyle’s moral ambiguity. Popeye Doyle plays by no gentleman’s rules, nor does he adhere to any moral code. In his world, survival is the only rule that matters.

A Decayed Yet Mesmerizing City

The New York of The French Connection is rotting from the inside, and the film does nothing to sanitize it. The city is grimy, worn down, and all the more powerful for it. Popeye Doyle and Cloudy Russo chase their targets down cracked sidewalks, while exhausted homeless people huddle in dark alleyways. Suspects are interrogated in burnt-out backstreets—New York itself becomes a crime scene.

Doyle’s apartment is the embodiment of urban decay: a dingy, claustrophobic tenement where nothing seems in order. Their precinct is no better—a bleak, gray office where they choke down cardboard-flavored pizza and coffee so vile that Doyle simply pours it onto the street. The city they are supposed to protect is filled with heroin-starved addicts, desperate for another fix, while drugs lurk in every shadowy corner. Pills, weed, and hash are stashed under bar counters, buried in coat pockets, or stuffed inside socks. At one point, an informant tells Doyle that an incoming heroin shipment will “make everybody well”—a chilling summation of how deeply addiction has consumed the city.

The grim, desolate world of New York starkly contrasts with the criminals smuggling heroin from France. Charnier and his associates are dressed in immaculate leather coats and stylish overcoats—even the cold-blooded assassin Nicoli wears a silk cravat. Charnier lounges in a villa overlooking the Mediterranean, stashing heroin in a luxury car, while Doyle and Russo rattle through the decaying metropolis in a battered, rusted police car. Yet Charnier is not a brash, ostentatious gangster in the vein of Tony Montana from Brian De Palma’s Scarface. Instead, he exudes quiet sophistication. Even in the middle of a high-stakes pursuit inside a rusted, abandoned warehouse, you can almost imagine Charnier meticulously dusting off his coat, unwilling to let the grime touch him.

The film’s final scene unfolds in an especially haunting location: a crumbling, hollowed-out building on a desolate lot on Ward Island, where rusted-out cars are auctioned off. The camera lingers on a cold, decayed hallway, possibly once a factory—leaving a final, lasting impression of a city in decline. Doyle disappears into the wreckage, chasing a criminal through a metropolis that is already lost.

The Art of Ugliness

When The French Connection hit theaters in 1971, critics praised its audacity in portraying how cops and criminals often operate with strikingly similar methods. This duality has since become a staple in crime films, perhaps reaching its peak with Michael Mann’s Heat in 1995. The French Connection received eight Academy Award nominations and ultimately won five: Best Picture (becoming the first R-rated film to claim the honor), Best Director for Friedkin, Best Actor for Hackman, Best Adapted Screenplay for Ernest Tidyman, and Best Film Editing for Gerald B. Greenberg.

The French Connection is more than just a gripping cop thriller—it’s a bleak yet mesmerizing snapshot of a city in decay, where the line between law and criminality blurs. The New York of the 1970s was a city on the brink, suffocating under economic collapse and rising crime. Since then, large-scale urban renewal has reshaped the city, as detailed by location scout Nick Carr on his blog, Scouting New York.

William Friedkin didn’t just make a pulse-pounding thriller—he crafted a raw, visceral portrait of a city whose beauty lies in its own destruction. The French Connection remains a searing reminder of New York’s darker past—and a testament to how ugliness, when framed by the right eye, becomes art.

– Gergely Herpai “BadSector” –

The French Connection

Direction - 10

Actors - 9.2

Story - 8.6

Visuals/Music/Sounds/Action - 10

Ambience - 10

9.6

MASTERPIECE

The French Connection is a prime example of raw realism and nerve-wracking intensity that transcends the traditional crime thriller. Hackman’s iconic performance and Friedkin’s brutally honest direction make it an unforgettable experience. Over five decades later, it remains just as suffocatingly tense and unrelenting as it was upon release.

Leave a Reply